Notes on Shawford Mill

by John A. Olive 1965

After the expected mention of mills in Rode in the Domesday Book (their site unknown) the first reference to “Sholdeford Mylls” is in 1516 when John Whitchurch was recorded as holding on a lease for life a mansion house and two water mills containing two stocks and a grist mill all under one roof. The term “stocks” originally used for troughs in which cloth was placed for fulling, had come to include falling hammers as well.

Like other industries, cloth-making had originated in the towns, partly for convenience, partly for security. Most of the power used was hand or foot, of the most laborious and important processes being the walking on the woven material to consolidate it.

Once it was realised mills that used to grind corn could also drive hammers to replace the “walkers” or “tuckers” the industry began to move out in the country to take advantage of the abundant water power, particularly in hilly areas such as the Mendips.

By the time that George Collins is recorded in 1609 as holding a lease of the property dated 10th March 1605, the family of Noad, which was to make and leave such a mark on Shawford, was established in Rode. John Noad and Margaret Langley were married at St. Lawrence church on 21st October 1599. Before the family’s rise to prominence however, in the next century, a great change had come over the industry. For a number of reasons the production ceased to be primarily of white cloth and was directed towards dyed cloth, which was sold in its finished state by the clothier. Not unnaturally dyeing came to be developed at sites where washing and scouring of wool were undertaken.

Since in this area cloth was largely dyed in the grain, not in the piece, the manufacture of West of England broadcloth in 1765 was as follows. The clothier bought wool, some English, some Spanish, through a London merchant. He had it cleaned and dyed and after making it up in “slubbings” he passed it to the spinners who brought it back as yarn, the spinning having been done in their homes, not only by the spinsters but by the married women as well. The yarn was then handed to weavers who again did the work at home mostly on looms of their own. The woven cloth was brought back to the mill to be fulled and then dried on racks in the field, which was known as “Rackham”. The final process of raising the nap and cutting it down to the finished surface was often carried out by a contractor who did work for several clothiers. Considerable strength as well as skill was needed to work the cutting shears and the shearmen could be dangerous enemies to clothiers wishing to introduce machinery. At all stages the materials remained the property of the clothier, whether or not he owned a mill or workshops.

Jonathan Noad was born in 1739 and had married Sally Whitaker, daughter of a well known local dyer in 1762. He was thus in business on his own account at the age of 24. He was not yet the owner of Shawford. “Mrs. Edwards of Sholveford” was buried in 1744 and John Edwards, (her son?), was still paying the land tax for “Shoalford” in 1788. Noad was assessed on four items in 1766 to a total of 18s 4d. He paid on 24 items in 1798, including Shawford, a total of £6 18s 3d and is described as proprietor and occupier. He became a churchwarden and overseer of the poor and at the death of his wife in 1809 was “esquire” and one of the most important people in the parish. He had recently rebuilt Shawford House for his second son, Humphrey Minchin Noad, and had Merfield House built on a piece of land “which I lately purchased of John Edwards” and bequeathed it in his will dated 1809 to his third son, Jonathan. He himself was then living in the picturesquely named house and factory of Rockabella. Southfield House, also rebuilt about the same time, was the home of his eldest son, Thomas Whitaker Noad, named after his grandfather who had left Shawford to Jonathan Noad senior in his will of 1781. Jonathan Noad senior died in 1814 and his slate tomb is on the south side of St. Lawrence church.

Shawford Mill was rebuilt as a factory in the early years of the 19th century when trade was still good and these are the remains we see today. By 1810 Humphrey Minchin Noad was living at Shawford and in that year enquired of Boulton and Watt the famous Birmingham engineers about the supply of a boiler and steam pipes for the more efficient heating of dyeing vats. This had been pioneered in 1799 at a woollen mill in Leeds and, nearer home, a Stroud firm ordered a steam heating plant in 1800. Noad’s enquiry seems to have been the first from this area. His works were much bigger than those at the Stroud firm, with eight vats each holding 1200 gallons. He was quoted by Boulton and Watt for a 12 hp boiler, 70 feet of 5 inch steam pipe, 8 stopcocks, 8 copper pipes and fitting, a total of £199 17s 7d. There is no record that he gave an order and he may have decided that with the nearest coal pit some 5 or 6 miles away the capital expenditure would not be recovered by savings in fuel costs for a very long time. There may also have been a fear that in this area with its strong tradition of high quality hand work the adoption of advanced technology would lead to a lowering of standards.

It has been said that Shawford mill was rebuilt by Mr. Parish, but that the property was the Noad family’s is quite clear from a marriage settlement drawn up by Humphrey Noad in 1810 referring to “all those 3 several messuages or tenements and also all those 2 several watermills thereto adjoining …. known by the name of Shoalford …. formerly in the possession of John Edwards and after that of Thomas Whitaker and late of John Parish”. If Parish did in fact build the mill it would have been as a tenant. Perhaps the Noads, like the Olives in Frome, were such successful dyers that they were able to retire early. Humphrey was called a dyer at the baptism of his eldest son in 1813; his brother Jonathan at Merfield was a clothier.

The West of England cloth trade never really recovered from the depression that followed the end of the Napoleonic wars. Just how bad conditions became is shown by Noad being compelled to mortgage some of his land in 1842. His widow mortgaged the whole property in 1845 after his death. However, this may well have been a convenient way to carry out his will, since the factory and house were let and in continuous occupation for the rest of the century. More significant are the extracts from Austin’s report to parliament on the state of weavers in 1840.

“The parish of Road near to, or adjoining, Frome contains 3 factories and 11 families of weavers possessing 18 looms; only one factory is at work. The average of the earnings of a single loom is stated to be 4s 9¼d. The children have very little employment and the amount per head per week for food and clothing is 11¾d.

“23 years ago (1817) the whole of the preceding great clothing district was in its most flourishing condition. That there is very considerable suffering and that many families (of weavers) are in worse condition (as regards food and clothing) than the inmates of a poor house, I have very little doubt.”

Not surprisingly the population of Rode fell from 954 in 1831 to 663 in 1878. On the other hand in reviewing the mechanical improvements in the other processes Austin states

“The weaver instead of suffering from these improvements was uniformly benefited by them.”

At the end of Humphrey Noad’s life Thomas Marks was carrying on a fulling business in the mill alongside the owner dyer, but this is the last reference to fulling at Shawford and the trade directories thereafter always give the occupiers as dyers. This change of use is made plain in an insurance inventory of 1854 made for William Willis of Shawford, dyer.

“Building formerly a woollen mill now occupied by Willis as an air drying stove and for store rooms, having a patent hydro extractor (or machine for drying wool by rotary motion) and indigo pots on ground floor, a bumble (or drying willey) on upper floor worked by water power only. Drying stove near heated by steam pipe from a boiler within the building but fire fed outside, drying stove near heated by stove with perpendicular pipe in centre of the building …. and furnace dyehouses.”

This W. Willis also appears as W. J. Willis and could be the J. Willis who is believed to have given the following information in 1861 listing dyehouses in Frome at the beginning of the century.

“The largest was at Shawford built by Mr. Parish and had 16 vats and 10 furnaces, Mr. Olive’s at Pilly Vale had 16 vats and 7 furnaces owned by Major Olive.”

The size of the largest vats shows further the importance of the Shawford establishment. They are described in a lease of 1874 as “to dye 700 lbs. of wool” and had a capacity of some 1200 gallons.

In spite of bad trade, improvements continued to be made at Shawford. Steam had been installed by 1844. Lawson the tenant added several small copper furnaces for pattern dyeing and one large one, which can be identified in the repairing lease granted to Edward Kemp in 1874. By this time the ownership of the property had become so entangled among the descendants of H. M. Noad and of the mortgagees, a clerical family of the name of Leir, that when Kemp wanted to buy he was instructed to pay the purchase money into the courts of Chancery pending the settlement of Noad v Leir 1883. He paid in all £2,700. When he went bankrupt in 1894 the creditors sold the place to W. O. Freeman for £500 together with an outstanding mortgage of £2,000. Mr. Freeman lived at Shawford, but he, like Kemp, had other interests at Freshford and Trowbridge, but Shawford ruined them both.

The coincidence of the publication of Mr. K. H. Rogers’ book “The Woollen Mills of Wiltshire and Somerset” with the coming of age (Old Style) of Shawford Opera has impelled me to put together material which I have gathered over a long period about the industry conducted here and the people concerned with it.

The materials that exist or have so far come to light are insufficient for a connected history but they are by no means negligible, as the references given below show.

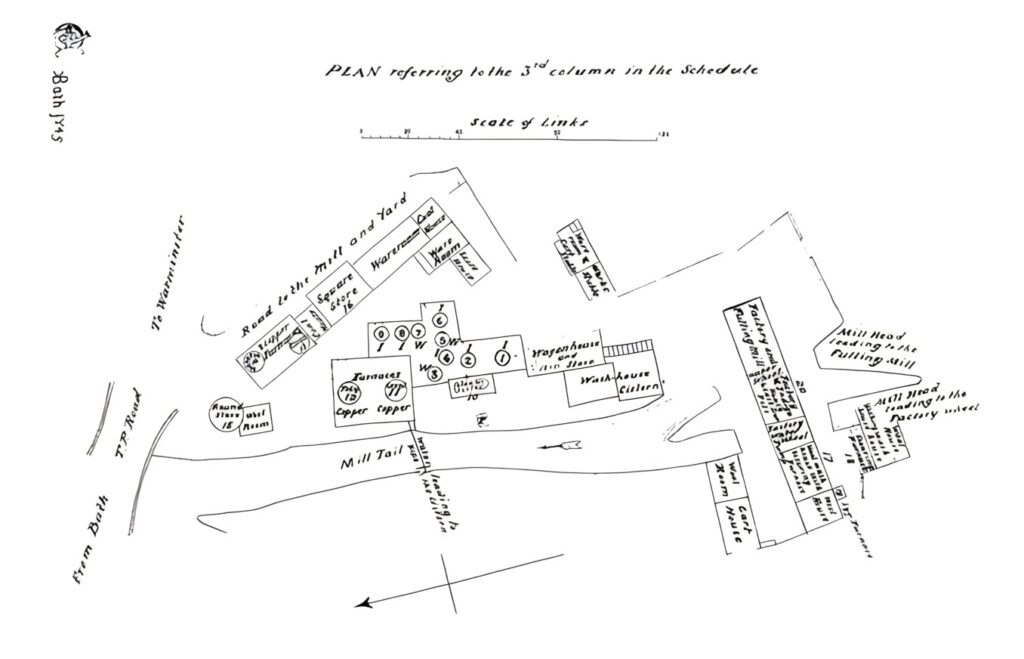

Noone driving down the old factory road to see an opera would guess that the whole area between him and the mill stream was once covered with buildings which on the plan (Plate I) make the mill proper look almost insignificant. The plan, taken from a lease of 1845, shows their exact position. They were mostly of one storey and contained vats for dyeing wool with furnaces under them. The largest even had official names as; Toby, Victoria, Caesar. The plan also shows that there were two mills in the same building, an indigo mill and a fulling mill, run independently of each other. What it does not show is that there were four storeys of which the present stage and auditorium was the first. Even if one assumes that the fourth was more in the nature of an attic with dormer windows, as a repairing lease of 1874 suggests, one still has to imagine a building twice as high to eaves level as the present one. When and why were two stories removed and the heavy roof replaced? The last industrial use of the place was as a laundry and dyeworks described as “extensive” in Kelly’s Directory. The works went bankrupt in 1899 since when Shawford has been purely a residence. One might suggest that Captain Heathcote, who bought the estate in 1900, had all the rest of the factory demolished and reduced the height of the mill so that it did not obstruct the view from the back of the house. Certainly the principle rafters are not in their original position standing as they do untenoned into the cross beams. A tiler once told me he had worked on the roof as a young boy during the first war but I was unable to verify this. Whether the year was 1900 or 1918 it speaks well for the workmen and their materials that the roof has had virtually nothing done to it for at least 60 years. Now that the skylights and gable have been repaired it looks good for as long again. Whoever it was who did the alteration, we can be grateful to him. Aesthetics and archaeology do not always clash, but they must have done so at Shawford with the mill at its full height.

After the expected mention of mills in Rode in the Domesday Survey (their site unknown) the first reference to Sholdeford Mylls” is in 1516 when John Whitchurch was recorded as holding on a lease for life a mansion house and two water mills containing two stocks and a grist mill all under one roof. The term “stocks”, originally used for troughs in which cloth was placed for fulling, had come to include falling hammers as well.

Like other industries clothmaking had originated in the towns, partly for convenience, partly for security. Most of the power used was hand or foot, one of the most laborius and important processes being the walking on the woven material to consolidate it. Once it was realised that the mills used to grind corn could also drive hammers to replace the “walkers” or “tuckers” the industry began to move out into the country to take advantage of the abundant water power, particularly in hilly areas such as the Mendips. It has also been suggested that the class of clothiers, capitalists who bought the wool and had it prepared, spun, woven and finished always under their own control, were keen to escape from the restrictive practices of the guilds who had come to control the various processes of manufacture in the towns.

By 1516 the export of cloth had long replaced that of wool as a main source of the national wealth. The great Perpendicular churches were many of them built by clothiers, but not by wool-men. Much of the cloth so exported was undyed and is still made in a special form as “blanquettes” at Witney. Beckington and Rode were famous for the whiteness of their cloths,2 many of which must have been produced by John Whitchurch at Shawford in his day.

By the time that George Collins is recorded in 1609 as holding a lease of the property dated 10 March 1605, the family of Noad, which was to make and leave such a mark on Shawford, was established in Rode. John Noade and Margaret Longley were married at St. Lawrence Church on 21 October 1599.3 Before the family’s rise to prominence, however, in the next century a great change had come over the industry. For a number of reasons the production ceased to be primarily of white cloth and was directed towards dyed cloth which was sold in its finished state by the clothier. Not unnaturally dyeing came to be developed at sites where washing and scouring of the wool were undertaken.

Since in this area cloth was largely “dyed in the grain” not in the piece the manufacture of a piece of West of England Broadcloth in 1765 was as follows. The clothier bought wool, some English, some Spanish, through a London merchant. He had it cleaned and dyed and after making it up into “slubbings” he passed it to the spinners who brought it back as yarn, the spinning having been done in their homes not only by the “spinsters” but by the married women as well. The yarn was then handed to weavers who again did the work at home, mostly on looms of their own. The woven cloth was brought back to the mill to be fulled and then dried on racks in the field where opera-lovers park their cars, which was known as “Rackham”. The final process of raising the nap and cutting it down to the finished surface was often carried out by a contractor who did work for several clothiers. Considerable strength as well as skill was needed to work the cutting shears and the shearmen could be dangerous enemies to clothiers wishing to introduce machinery.4 At all stages the materials remained the property of the clothier, whether or not he owned a mill or workshops.

That something like the above is what was happening at Shawford is shown in a series of letters from a London factor who was buying cloth from Jonathan Noad. The series runs from 1763 to 1769 with an almost weekly frequency. Noad was born in 1739 and had married Sally Whitaker, daughter of a well-known local dyer in 1762. He was thus in business on his own account at the age of 24. He was not yet the owner of Shawford. “Mrs. Edwards of Sholveford (note the intrusive ‘l’) was buried in 1744 and her son(?) John Edwards was still paying part of the Land Tax for “Shoalford” in 1788. Noad was assessed on 4 items in 1766 to a total of 18s 4d. He paid on 24 items in 1798, including Shawford, assessed to a total of £6 18s 3d and is described as proprietor and occupier.5 He became Church-warden and Overseer of the Poor and at the death of his wife in 1809 was “Esquire” and one of the most important people in the parish. He had recently rebuilt Shawford House for his second son, Humphrey Minchin Noad, and had Merfield House on a piece of land “which I lately purchased of John Edwards” and bequeathed it in his will dated 1809 to his third son Jonathan. He himself was then living in the picturesquely named house and factory of Rockabella. Southfields, also rebuilt about the same time, was the home of his eldest son, Thomas Whitaker, named from his grandfather who had left Shawford to Jonathan Noad under his will of 1781. Noad died in 1814. His slate tomb is on the south side of Rode church.

Unfortunately the correspondence referred to above is one-way only. One can gather that neither Noad nor his correspondent, James Elderton, were given to mincing their words. Elderton is constantly rebutting Noad’s complaints about the cost of wool he has bought for him or warning him that his cloth is so badly dressed that he ought to get another dresser, but he also asks Noad to recommend him to a manufacturer of medleys and to speak for him to Mr. Whitaker, and he always discounts Noad’s bills without demur and declares that his house is at Mrs. Noad’s disposal whenever she is in town.

By the middle of the century the Blackwell Hall factors, of whom the firm of Elderton and Hall were one, were facing strong com-petition from other outlets for the marketing of cloth and Elderton complains to Noad of his selling his cloth direct to Bristol and elsewhere and threatens to break off relations with him. He was probably fighting a losing battle. Blackwell Hall as a market for cloth decayed so much that it was demolished in 1819. It lay between Basinghall Street and King Street with a frontage on Guildhall Yard. Just before its demolition it was drawn by the topographical artist Robert Schnebbelie, whose drawings may be seen in the print room of the Guildhall Library.

Shawford Mill was rebuilt as a factory in the early years of the 19th century when trade was still good, and these are the remains which we see today. Some earlier walling and windows survive in the south-western part. (PlateII). By 1810 Humphrey Minchin Noad was living at Shawford and in that year enquired of Boulton and Watt, the famous Birmingham engineers, about the supply of a boiler and steam pipes for the more efficient heating of dyeing vats. This had been pioneered in 1799 at a woollen mill in Leeds, and, nearer home, a Stroud firm ordered a steam heating plant in 1800. Noad’s enquiry seems to have been the first from this area. His works were much bigger than the Stroud firm’s, with 8 vats each holding 1200 gallons. He was quoted by Boulton and Watt for a 12hp boiler, 70ft of 5in steam pipe, 8 stop cocks, 8 copper pipes and fitting a total of £199 17s 7d.6 There is no record that he gave an order and he may have decided that with the nearest coal-pit some 5 or 6 miles away the capital expend-iture would not be recovered by saving in fuel costs for a very long time. (It would cost him some £16 13s per boiler horsepower whereas in a large installation this could be as low as £7 5s). There may also have been a fear that in this area with its strong tradition of high quality hand-work the adoption of an advanced technology would lead to a lowering of standards.

It has been said that Shawford mill was rebuilt by a Mr. Parish, but that the property was the Noad family’s is quite clear from a marriage settlement drawn up for Humphrey Noad in 1810 referring to “all those 3 several messuages or tenements and also all those 2 several watermills thereto adjoining …. known by the name of Shoalford …. formerly in the possession of John Edwards and after that of Thomas Whitaker and late of John Parish”. If Parish did in fact rebuild the mill it would have been as a tenant. Perhaps the Noads like the Olives in Frome were such successful dyers that they were able to retire early. Humphrey Noad is called a dyer at the baptism of his eldest son in 1813. His brother Jonathan at Merfield was a clothier.

The West of England cloth trade never really recovered from the depression which followed the end of the Napoleonic wars. Just how bad conditions became is shown by Noad’s being compelled to mortgage some of his land in 1842. His widow mortgaged the whole property in 1845 after his death. However, this may well have been a convenient way to carry out his will, since the factory and house were let and in continuous occupation for the rest of the century. More significant are the extracts from Austin’s report to Parliament on the state of weavers in 1840.

“The Parish of Rode near to, or adjoining, Frome contains three factories and 11 families of weavers possessing 18 looms; only one factory is at work. The average of the earnings of a single loom is stated to be 4s 9¼d. The children have very little employment and the amount per head per week for food and clothing is 11¾d.

“Twenty three years ago (1817) the whole of the preceding great clothing district was in its most flourishing condition.” “That there is very considerable suffering and that many families (of weavers) are in a worse condition (as regards food and clothing) than the inmates of a poor house I have very little doubt.”7

Not surprisingly the population of Rode fell from 954 in 1831 to 663 in 1878. On the other hand in reviewing the mechanical improve-ments in the other processes Austin states “the weaver instead of suffering from these improvements was uniformly benefited by them.”

At least in 1828 somebody was still at work here when two brothers-in-law practised lettering on one of the window boards (Plate III). This was showing some pride in a newly acquired skill. When Richard Greenland married James Short’s sister in 1819 neither of them could write their names.

At the end of Humphrey Noad’s life Thomas Marks was carrying on a fulling business in the mill alongside the owner dyer. The plan of 1844 (Plate I) shows which premises he occupied, but this is the last reference to fulling at Shawford and the Trade Directories thereafter always give the occupiers as dyers. This change of use is made plain in an insurance inventory of 1854 made for William Willis of Shawford, dyer.

“Building formerly a woollen mill now occupied by Willis as an air drying stove and for store rooms, having a patent hydro extractor (or machine for drying wool by rotary motion) and indigo pots on ground floor, a bumble (or drying willey) on upper floor worked by water power only. Drying stove near heated by steam pipe from a boiler within the building but fire fed outside. Drying stove near (Plate IV) heated by a stove with a perpendicular pipe in centre of the building …. and furnace dyehouses.”

This W. Willis also appears as W. J. Willis and could be the J. Willis who is believed to have given the following information in 1861 listing dyehouses in Frome at the beginning of the century. “The largest was at Shawford built by a Mr. Parish and had 16 vats and 10 furnaces. Mr. Olive’s (my great great grandfather) at Pilly Vale had 16 vats and 7 furnaces and employed 52 men, In Justice Lane 7 vats and 4 furnaces owned by Major Olive.”8

The size of the largest vats shows further the importance of the Shawford establishment. They are described in a lease of 1874 as “to dye 700 lbs. of wool” and had a capacity of some 1200 gallons.9

In spite of bad trade improvements continued to be made at Shawford. Steam had been installed by 1844 and it seems almost certain that the large boiler (Plate V) now at Peart Farm which is known to have come from Shawford is the one marked on the plan (Plate I). Lawson the tenant added several small copper furnaces for pattern dyeing and one large one which can be identified in the repairing lease granted to Edward Kemp in 1874. By this time the ownership of the property had become so entangled among the descendants of H. M. Noad and of the mortgagees, a clerical family of the name of Leir, that when Kemp wanted to buy he was instructed to pay the purchase money into the Court of Chancery pending the settlement of Noad v Leir 1883. He paid in all £2,700. When he went bankrupt in 1894 the creditors sold the place to W. O. Freeman for £500 together with an outstanding mortgage of £2,000. Mr. Freeman lived at Shawford and one of his two surviving daughters was born here. Freeman, like Kemp, had other interests at Freshford and Trowbridge, but Shawford ruined them both.

Edward Olive, the successful dyer, contemporary of H. M. Noad, and owner of the largest dyeing establishment after Shawford, was descended from at least six generations of John Olives (one was a William John) stretching back to 1585. His father was described as a dyer when he married Ann Rossiter in 1758.10 She was the daughter of William Rossiter, a clothier. Edward himself married Betty Crabb daughter of William Crabb, a clothier of Tellisford. His son Edmund Crabb Olive was the last of the name to live in Frome. He was a non-practising solicitor and married Eliza Daniel, sister of the first vicar of Trinity Church, Frome.

There were thus no traces of a family which had been prominent in the clothing trade in the small Somerset town when the present generation of Olives and their parents returned to the area in 1938 Was it fate or coincidence that led them to Shawford?

On a fine spring afternoon in April 1933 my brother Theo and I were journying from Gloucester into Dorset. We had refreshed ourselves at the “George” in Norton St. Philip and, as a diary kept by Theo at the time shows, had got into conversation with an oldish man who remembered Dr. Parsons of North End House, Frome, whose sister Polly had married Charles Daniel Olive of “The Chest-nuts” opposite. (The site is now used by a government department). We were of course aware that great-grandfather Joshua Parsons was called out in the Rode murder case (and family tradition has a rather different story from some later accounts). Thus, slightly drowsy and in a musing mood, we elected to stop and lie under a wall overlooking an orchard just coming into bloom, which reminded us of the painting by Alfred Parsons R.A. in the Tate Gallery called “When Nature painted all things gay”, and we said to ourselves that this would indeed be a pleasant place in which to live. (There is now a lay-by at this point, which is some 300 yards up the road). Needless to say when in 1938 our parents, after looking at a number of properties, came to see Shawford, we all insisted that they should take it. Its run-down state and lack of almost any modern convenience such as we knew in London were in our eyes more than offset by the charms of the river, the mill and the other out buildings.

The house had since 1919 been the home the Lechmere family, who in due course had returned to their estate in Worcestershire upon Captain Lechmere’s inheriting the baronetcy. The builder’s records show that they did remarkably little work on the place during the years to l937 when the house became vacant.11 The garden however was well maintained. A Silverlite petrol gas machine had been installed, water was pumped from the river by a small water-wheel brought from the Worcestershire estate and still in 1977 in working order (Plate VI); sewage was discharged into the mill tail. Drinking water was pumped by hand from a well which has yet to be discovered.

Repairs and modernisation were put in hand at once, and nearly as much spent as the £1,800 which the estate had cost. (It is interesting to note that the place was again brought up to date in 1969 by the present owners, Roy and Fanny Coleman. What will be the improvements thought to be essential in 1999?). On many of the outbuildings we set to work ourselves during weekends from London and thus, many years before Do It Yourself or Industrial Archaeology were invented, we were involved in them in a practical way.

As has been stated above, the mill itself had a roof in very fair repair. There were three skylights which had fallen in so that all floors beneath were rotten. The western end was covered with ivy standing out several feet from the wall. We felt that we had just arrived in time. It is worth remaking that neighbouring mills still had some roofing at this time. They are now no more than heaps of rubble. The second waterway was put to use when a turbine was installed driving a DC generator, as it still does. Further use of the mill, except as a store, had to wait for many years. The public supplies of water, gas, and electricity were not available until after the war.

For those of us who live here the charm of Shawford has always been its completeness. Bounded on one side by the main road and on another by the river meeting it, and on the third by a small stream, it has its weir with the millstream giving power to the mill, the mill itself and traces of other industrial buildings, the field where the cloths were dried and, most notably, the house in which the factory owners dwelt. I do not believe that this set-up remains so clearly shown anywhere else on the river Frome.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

1. Eileen Power in “Medieval People Thomas Paycocke of Coggeshall”.

2. The late E M Carus-Wilson asked me if I could give a reason for this. I do not know her authority for the statement.

Somerset Records Office Rode Parish Registers.

K. G. Ponting, “Wool and Water” pp 22-23.

S. R. O. Land Tax Assessments.

Birmingham Reference Library, Boulton and Watt MSS Portfolio 1834

State Papers 1840 Vol. XXIII 49.367.

8. S. R. O. DD/LW 37.

9. Document in possession of Mr. Peter Quartley

10. Document in my possession.

11. Ledgers of Colborne and Sons Hinton Charterhouse.

DOCUMENTARY SOURCES

Apart from those referred to in the notes there exists a list of documents to be exhibited in the Chancery case of Noad v Leir 1883 Those from 1809 onwards are in the possession of Mr. Peter Quartley to whom I am indebted for a long loan of them. The earlier ones have yet to come to light.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

MANN, J de L., The Cloth Industry in the West of England. Oxford 1971.

PONTING, K. G., A History of the West of England Cloth Industry. 1957.

PONTING, K. G., Wool and Water. Bradford 1975.

ROGERS, K., Wiltshire and Somerset Woollen Mills. Edington 1976.

TANN, J., A Practical Treatise on Dying. 1823, reprinted Edington 1973.

To all the above, except the late William Partridge, I am most grateful for help and information. They are the leading authorities on the subject and have all taken a personal interest in Shawford. I have little more than put together their references in compiling these notes.

WORK ON SHAWFORD MILL 1939 to 1977

We have always felt that the limited use to which we intended to put the building precluded a sophisticated theatre and that no more than essential expenditure was justified, even if it were possible. Our aim has been to leave the building in good repair but otherwise very much as found it.

Skylights repaired, much ivy removed. Windows in the turbine house. repaired with the addition of a coloured glass light by Theo Olive representing “water power”.

Steps built to south door, replacing wooden staircase hitherto the sole access to the first floor.

All floors and first floor windows repaired. Stage partly raised.

to Auditorium arranged in tiers. This was and remains the chief alteration

1957 to the interior.

1957 Steps and entrance at east end built. The stonework of the doorway being the only job not undertaken by family labour. The experience of the first production in July of this year showed the necessity for this the only “improvement” to the exterior.

1958 The pit, formed by removal of one section of the first floor, was lowered.

1959 The orchestra found its proper level at the bottom and the pit could then be extended under the stage. Apart from the cold and damp, playing conditions have always been pronounced to be good.

Two sections of the upper floor removed to form a gallery.

1966 The whole stage lowered to original floor level.

1971 The “green room”’ added to the west wall. This is useful for production but not an embellishment. It can easily be removed.

IMAGES

I Shawford Works in 1844. This is an exceptionally detailed and beautifully drawn plan.

II Windows of two periods. Early 18th? and early 19th centuries

III Alphabet carved by James Short. Richard Greenland’s name also can be read in a favourable evening light on the head of a window on the South wall

IV Remains of one of two circular wool-drying stoves in Frome both formerly belonging to the Olive family. There was a similar one at Shawford and also a square one. They had conical roofs. Their form exactly corresponds to Partridge’s description pp 34-36. See bibliography.

V Boiler, upside down, as storage tank at Peart Farm. The plates are small and of wrought iron, an indication of an early date.

VI Waterwheel, probably early 20th century, with pump, all in working order.