[By Chloe Wells, academic researcher, published on Medium]

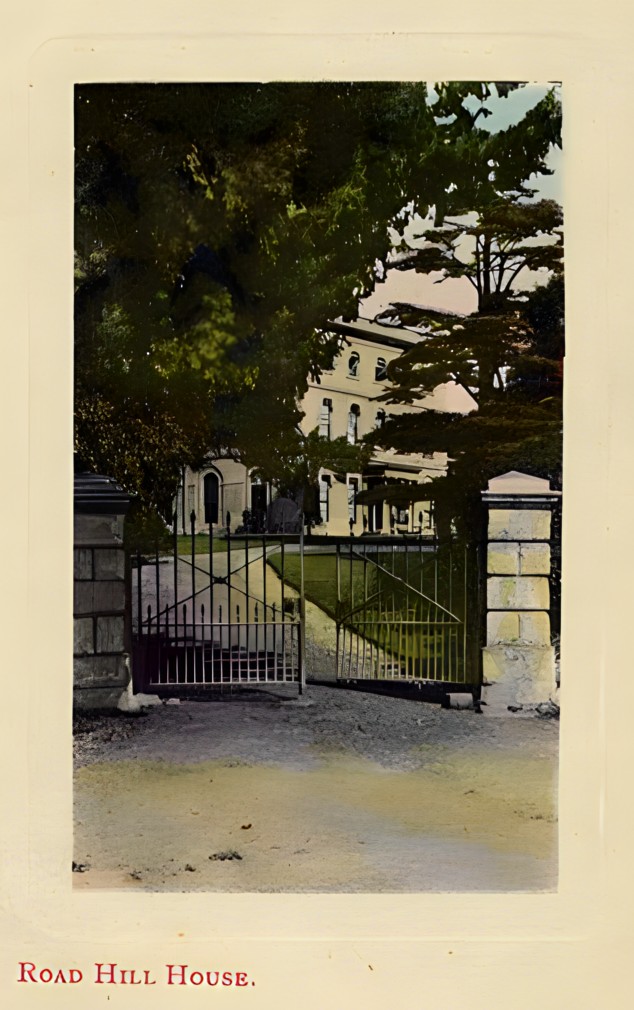

Road Hill House in Road, Wiltshire is surrounded by walls, fences, and a high gate newly installed by the house’s latest occupant — a Mr Samuel Saville Kent — to deter locals from ‘scrumping’ (stealing) apples from its orchard.

In June 1860 the weather in England is unusually terrible: rainy and stormy. And, unbeknownst to all but one of the Kent household, a murder is about to be committed at Road Hill House.

The Kent Household in June 1860

In June 1860, the following people are living at Road Hill House: Mr Samuel Saville Kent age 59, an Inspector of Factories for the Home Office; his second wife Mrs Mary Kent 40, mother of three and heavily pregnant with her fourth child; Mary Ann Alice Kent, 29, Elizabeth Kent, 28, and Constance Emily Kent, 16, daughters from their widowed father’s first marriage; William Saville Kent, 14, son from his widowed father’s first marriage (William and his sister Constance were away at their boarding schools during term time but are currently home for the summer holidays); Mary Amelia Kent, 5, and Eveline Kent, 1, daughters of Samuel and Mary Kent; and Francis Saville Kent, 3, son of Samuel and Mary Kent.

There are also three live-in members of staff at Road Hill House: nursemaid Elizabeth Gough, 22, who cares for the three younger children; Sarah Cox, 22, housemaid; and 23-year-old Sarah Kerslake, who was the cook.

The live-out employees are: 14-year-old Emily Doel, who assists Elizabeth Gough with childcare from 7.00 am – 7.00 pm, and James Holmcome, 49 and his assistants Daniel Oliver, 49 and John Alloway, 18 who take care of the gardens, grounds, and stable of the house.

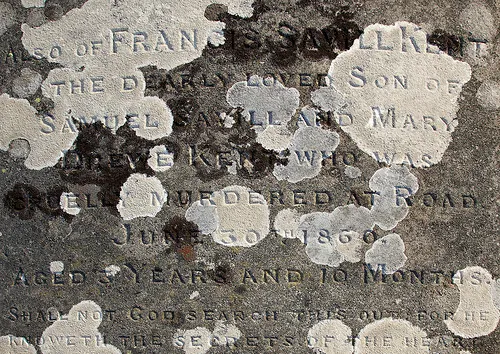

Missing and murdered: Francis Saville Kent, age 3.

The evening of 29th June was by all accounts like any other at Road Hill House. In the evening the daytime staff left as usual, with Holcome locking the tall gate set into the high walls which surrounded the house behind them.

The nursemaid Elizabeth Gough put Francis Saville Kent — known to the household as Saville — who was almost four years old, to bed in the nursery at 8.00 pm. By 10.00 pm, only Mr Kent was still up. He wandered the house and checked that all the doors and windows were locked and bolted before going to bed at around 11:30 pm.

At around 1.00 am the household’s guard dog let out a few barks, but this was not unusual and was ignored.

Sunrise on Saturday 30th June was around 3.50 am. At 5.00 am groundsman Holcolme arrived for work, unlocking the gate, chaining up the guard dog and heading to the stables.

Around the same time, Elizabeth Gough awoke in the nursery to see that Saville’s cot was empty, and the cot’s sheets neatly folded. She was not immediately concerned, assuming that the child’s mother had come to fetch him during the night and taken him to her own room.

At 6.00 am Sarah Kerslake, the cook and Sarah Cox, the maid began their day’s work. Sarah Cox went about unbolting and unlocking the doors and windows of the house. When she reached the downstairs drawing-room she noticed that the door had already been unlocked and that the middle sash window was partly open. Assuming someone had simply been airing out the room, she closed the window and continued her morning routine.

At 7.00 am Elizabeth Gough knocked on the door of Mr and Mrs Kent’s bedroom to retrieve Saville. Mrs Kent told her that he was not in the room. Elizabeth then checked with the other Kent children to see whether Saville was with them. By 7.30 am they realised that the little boy was not anywhere in the house.

Mr Kent alerted Holcome that young Saville was “Lost, stolen and carried away”, and ordered the household’s staff to search for him. Mr Kent sent assistant groundsman Alloway to fetch the village policeman, William Kent was dispatched to fetch the local parish constable, and Constance Kent was ordered to fetch the local priest. Mr Kent then left to ride the five miles to the nearby town of Trowbridge, Wilshire to inform Police Superintendent John Foley that Saville was missing.

As the grounds were being searched, two local men named Nutt and Benger, who had arrived to help in the search, noticed a small pool of blood outside the staff privy (outside toilet) in the gardens of the house. Reaching down into the privy they pulled out a large bundle. It was the body of Saville, wrapped in a blood-soaked blanket from his cot. The child, who was still dressed in his nightshirt, had a very deep gash across his throat. He also had a stab wound to the chest and bruising around his mouth. Benger carried Saville’s body up to the house.

William Kent was again dispatched, this time to fetch the family’s doctor from a village two miles away. When the doctor arrived he inspected the body and estimated the time of death as having been at about 3.00 am.

At 10.00 am, Superintendant John Foley arrived at Road Hill House. He inspected the entire building and all the clothing of the residents but found nothing suspicious.

Above: Francis Saville Kent’s grave, Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Coulston, Wiltshire,

Local police arrest the Nursemaid

The local police, villagers, and the press quickly concluded that, as the Evening Standard put it the following Monday:

“From the manner in which the child was taken away and murdered… the deed was done by some inmate of the house”

Suspicion primarily fell on the nursemaid, Elizabeth Gough. She was the last known person to have seen Saville alive and local police found it incredible that she could have slept through his abduction. Mrs Kent, however — though believing the guilty party was a member of her household — did not believe Elizabeth could be guilty. Elizabeth was arrested at Road Hill House on July 10th, ten days after Saville was killed. She was later freed after no evidence could be found to send her to trial for the murder.

With an outcry in the national press over the killing, the famous Detective Jack Whicher of London’s Scotland Yard was sent to rural Wiltshire to investigate, arriving in Road on July 14th.

Jack Whicher: “Prince of detectives”

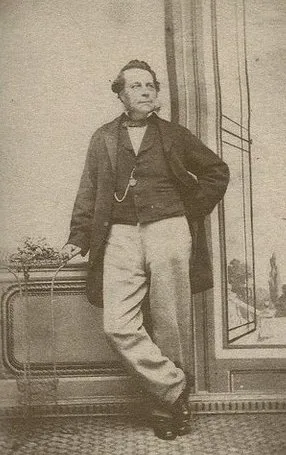

Detective Jack Whicher. Image: Wikipedia.

By the time working-class Londoner Jack Whicher arrived in Road in 1860 the 46-year-old Detective had already solved several notorious crimes and had gained a reputation for being able to solve even the most difficult cases.Jonathan ‘Jack’ Whicher was born in London in 1814. He was 5 ft 8 inches (1.73m) tall, with brown hair, bright blue eyes and pale skin scarred by smallpox.Whilst his colleagues at Scotland Yard regarded him as the “prince of detectives” he was also described by none other than Charles Dickens as possessed of “a reserved and thoughtful air, as if he were engaged in deep arithmetical calculations.”

A teenage murderess?

In Road, Whicher quickly established that the open window downstairs, suggesting an outsider had broken in and taken Saville, was a ‘red herring’ and his suspicion fell on 16-year-old Constance Kent, the murdered child’s older half-sister from their father’s first marriage.

Constance was her father’s fifth daughter and ninth child with his first wife Mary Ann who had died eight years earlier in 1852 age 44 when Constance was only eight years old. Rumours abounded that Mary Ann Kent had been mentally ill, made unwell by bearing her husband ten children in 16 years, four of whom died in infancy. Mrs Kent had in fact been diagnosed with “weakness”, “bewilderment of intellect” and “various, though harmless, delusions.” After the deaths of the four babies, Mr Kent hired 24-year-old Mary Pratt to be the family’s governess. Mary more or less raised Constance and her younger brother William from birth as their mother was too unwell to do so.

There were also rumours that Mary Pratt and Mr Kent had become lovers before his first wife’s death. Mary had taken on a central role in running the household whilst the first Mrs Kent was still alive. Mr Kent married Mary in August 1853, 15 months after the death of the first Mrs Kent. The following June Mary gave birth to a stillborn child. The couple’s next child, Mary Amelia was born the following year.

Constance had not been happy at home. Three years before the murder, Constance, then aged 13, had run away from home with her brother William, then aged only 11. After cutting off her hair and changing into boys’ clothing she and William headed for the port city of Bristol, 30 miles north-west of Road, hoping to board a ship out of the country. They were found 9 miles away in a hotel in Bath and returned home.

The Suspicions of Mr Whicher

Detective Whicher suspected Constance for several reasons:

Firstly, Whicher was certain that the murderer had to be a member of the household. Constance slept alone in her own room and had, according to Whicher, both the physical strength and mental fortitude to commit the crime: “She appears to have a very strong mind” he wrote in a five-page letter to the Commissioner at Scotland Yard outlining his suspicions. At the same time, Whicher also held the belief common in Victorian England that mental illness could be inherited. Because Constance’s mother had been mentally ill, he suspected Constance of also being unstable.

Secondly, one of Constance’s nightgowns was missing. This had been noted shortly after the murder by the Kent’s laundress, who had told Mr Kent about it but not told the police.

Thirdly, when Constance had attempted to run away from home three years before, she had hidden her hair cuttings and clothes inside the same privy where Saville’s body had been found.

On Friday, July 20th, Whicher arrested Constance at Road Hill House. When arrested, she began to cry: “I am innocent, I am innocent” she repeated. Constance appeared before the magistrate who placed her into custody for seven days at Devizes, Wiltshire, 16 miles east of Rode, whilst Whicher continued his investigation of the case. Whicher needed proof of motive and he also needed to find the missing nightgown.

“There was not a tittle of evidence against her”

Despite Whicher’s best efforts, the nightgown was still missing when the inquiry into Saville’s murder reconvened on 27th July. Elizabeth Gough was called to give evidence. She stated:

“During the whole of the time that I have been in Mr Kent’s service I have never heard Miss Constance say anything unkind towards the little boy that is dead.”

Constance’s school friends and other servants also felt the same: that Constance had not expressed animosity towards Saville.

Whicher lacked credible proof of the motive for the murder having been a mentally unstable Constance’s murderous envy towards Saville for being her father’s favourite child.

Mr Kent had engaged the services of an experienced barrister from Bristol, Mr Peter Edlin, to defend his daughter. Edlin gave a thundering speech at the inquiry including the assertion, in the language of the time that:

“There was not a tittle of evidence against her… (and yet) this young lady had been dragged like a common felon to Devizes Gaol… (No) motive (has) been established which would induce the prisoner to (stain) her hands in the blood of the poor child…A more unjust, a more improper, a more improbable case…was never brought before any court of justice in any place”

Influenced by this speech, the jury decided there was not enough evidence for Constance to stand trial for the murder and she was released from custody.

Throughout this saga, the national and local press — who had highlighted Mr Kent and Elizabeth Gough as suspects — had supported Constance and had been critical of Whicher and the whole ‘Detective Branch.’ The Wiltshire & Devizes Gazette for example stated in an editorial on August 2nd that:

“We do not believe that there is a single human being besides Mr Whicher who would think it sufficient to detain (Constance Kent) in custody for a minute…there was no occasion whatever for calling in the assistance of a Metropolitan functionary (i.e. a detective). Our own excellent police have at all times shown themselves entirely competent to their duties;…the ends of justice would have been much better answered if they had not been interfered with.”

Whicher returned to London having not managed to solve the case and having damaged the reputation of Scotland Yard’s Detective Branch. It took some time for his reputation to recover.

The local police later again arrested nursemaid Elizabeth Gough for the murder but the case against her also collapsed before it went to trial.

Another magistrate, Thomas Bush Saunders from nearby Bradford-on-Avon, Wiltshire, then took it upon himself to open his own inquiry into the case. Despite being described as a “crack-brained boggler” and a “meddling, vain old idiot” Saunders’ inquiry managed to reveal one crucial fact: the local police had in fact found what appeared to be the missing nightdress hidden at Road Hill House the very day after the murder. Local policeman Alfred Urch told the court the garment was “dry but very dirty…it had some blood about it.” Urch had handed the garment to Superintendent Foley but he dismissed it as evidence, believing it was stained with menstrual blood and had been hidden out of shame.

In 1861, the Kent family moved away from Rode. Constance was sent to a finishing school and then to a convent in France and William returned to his boarding school. Elizabeth Gough had left the family’s employ in August 1860.

…

Confession

In 1863 Constance, now aged 19, moved to Brighton to live at St Mary’s, a house for ‘religious ladies’, where she stayed for the next two years.

On April 25 1865, Constance Kent, now aged 21, walked into London’s Bow Street Magistrates’ court and handed over a hand-written confession:

“I, Constance Emilie Kent, alone and unaided on the night of the 29 of June 1860, murdered at Road Hill House, Wiltshire, one Francis Saville Kent. Before the deed, none knew of my intention, nor after of my guilt, no one assisted me in the crime, nor in my evasion of discovery.”

Constance was convicted of the murder and sentenced to death by hanging, only to be reprieved by Queen Victoria. She went on to serve 20 years in prison before being released in July 1885, at the age of 41. In early 1886 she emigrated to Australia under a new identity.

In Australia, Constance trained and worked as a nurse including on a leper colony and at a home for young offenders. She died aged 100 in 1944.

Was she guilty?

Despite Whicher’s suspicions and Constance’s confession, there were those, including Charles Dickens, who thought it more likely that her father was guilty. The theory was that Mr Kent, a known adulterer, was sleeping with the 22-year-old nursemaid Elizabeth Gough and had murdered his son in a rage when the boy interrupted the two of them. Mr Kent told police he had stayed up late, alone, on the night of the murder. He also rode away during the search for his son — the perfect opportunity to dispose of any incriminating evidence. Whilst Constance, William and the groundsman Alloway had also gone off the property that morning, also giving them the chance to dispose of evidence, their leaving had been on Mr Kent’s orders.

Mr Kent himself favoured an outsider as the culprit. He claimed that others besides the current household could have known the layout of the house and grounds and could have abducted and murdered Saville due to a hatred of Mr Kent, who was disliked in the village and local area.

The local police, and journalists, suspected the nursemaid Elizabeth Gough. Their theory was that she was having an affair, either with Mr Kent, a male member of the household staff, or another unknown person and that young Saville — who was old enough to talk — had witnessed her with the man. He was murdered to silence him. Police and others were doubtful that Elizabeth could have slept through Saville’s abduction from their shared bedroom, as she claimed. The bruises around Saville’s mouth indicate he was smothered or suffocated before his throat was cut.

Another theory, put forward by Kate Summerscale in her 2008 bestselling book The Suspicions of Mr Whicher or The Murder at Road Hill House, is that Constance’s younger brother William, with whom she was very close, was either guilty or was Constance’s accomplice and that Constance confessed in order to cover for him. William was a suspect at the time of the murder but was never arrested. Detective Wicher also suspected that William was an accomplice or at least a confidant of Constance.

Summerscale concludes that, whoever was guilty, the motive was revenge against Mr Kent, who favoured his children by his second wife, of whom Francis was his favourite.

Postscript

The Kents had two more children after Saville’s death: Acland Savill Kent, born just a month after his brother’s murder in July 1860, and Florence Savill Kent, born the following year. Mrs Kent died in Wales in 1866 aged just 46. Mr. Kent died in Wales, where he had moved his family after the murder, in 1872 aged 70.

Detective Whicher left the police force in 1864. On his papers, his reason for early retirement was given as “congestion of the brain.” Whicher died in London in 1881 age 67. The real-life Detective’s character and skill formed the blue-print for fictional detectives including Charles Dickens’s Inspector Bucket and Colin Dexter’s Inspector Morse.

Whicher’s investigation into the murder of Francis Saville Kent has been the subject of the bestselling book The Suspicions of Mr Whicher or The Murder at Road Hill House by Kate Summerscale (2008) and of the feature-length dramatisation The Suspicions of Mr Whicher: The Murder at Road Hill House (2011).